Stealing Christmas: the Gift Exchange Game

The tradition of exchanging gifts in a game-like format has multiple regional names across the United States, including ‘White Elephant’, ‘Yankee Swap’, and ‘Dirty Santa’, along with more colorful variations such as ‘Thieving Elves’, and ‘Cutthroat Christmas’. While the modern practice centers on exchanging either practical items or deliberately impractical gifts in an entertaining format, its origins can be traced to early American ‘swap parties’ documented as far back as 1901 in The Hartford Herald.

Tomorrow, many people will gather in living rooms and office breakrooms for a familiar ritual. The rules are simple: open a gift, or steal one. The dynamics are a mesh of game theory, social friction, and positional advantage. In two minutes, the rules may be explained; the strategic depth, however, rivals games people spend years mastering. There is hidden information (wrapped gifts), sequential play (turn order matters enormously), and a social layer that no rulebook captures (indeed, stealing a gift from Grandma has costs that do not otherwise appear in any matrix or functional representation).

I wrote formal proofs of the game’s mechanics, defined the state space, and ran 240,000 simulated games with artificial players that (attempt to) model human pettiness. Here is what I learned.

Note: please see similar work by Ben Casselman and Sean Falconer for additional material on simulating the gift exchange game. The paper and code associated with this post are found at the GitHub repo.

Combinatorial explosion

First, let us appreciate why this game feels chaotic: stealing chains.

When Player A steals from Player B, Player B is “displaced” and must act: they can open a wrapped gift (ending the chain), or steal from someone else (extending the chain); if they steal from Player C, who steals from Player D… and so we get a recursive cascade of thievery. The only rule preventing infinite loops: you cannot immediately steal back the gift that was just taken from you.

I derived the formula for counting distinct game trajectories, every unique sequence of decisions from start to finish; the complexity explodes:

| Players | Possible trajectories |

|---|---|

| 3 | 60 |

| 5 | 1,248,000 |

| 8 | 3,670,000,000,000,000,000 |

That last number is 3.67 quintillion. For context: if you played one game per second since the Big Bang, you would not have covered 1% of the possibilities for an 8-player game.

If you have ever felt like your game “went off the rails,” you were experiencing genuine mathematical complexity; indeed, the probability of replaying an identical trajectory is vanishingly small.

The per-round action counts follow OEIS sequence A000522, the same sequence that counts arrangements of n elements where no element stays in its original position. Why does a stealing chain formula match a fixed-point-free permutation formula? Worth thinking about.

The Simulation; or, modeling human pettiness

Let us be forthright: human interactions are complicated. Math describes the mechanics, but not the vibes. Game theory can tell us the Nash equilibrium of poker, but it cannot tell us why my uncle goes all-in with seven-two offsuit after his third drink of the night (or, morning, as is sometimes the case).

To understand real play, I built a “decorated game” model with psychologically plausible agents; behavior in humans, however, is difficult to model, so the assumptions made here and their proxies are certainly brittle under scrutiny, but I do think they are plausible enough to be useful, or, at least, entertaining, as far as this project goes. Humans are not hyperrational utility maximizers; rather, humans are petty, emotional, and they judge books by covers.

The features I modeled:

-

Social Costs: stealing is not free; every theft costs “relationship points”, essentially a base cost for norm violation, plus escalating penalties for repeat offenses against the same victim. Stealing from your boss once could well be awkward, if humorous; stealing from her twice, however, or thrice, is a statement.

-

Frustration-Aggression: agents that got stolen from became more aggressive on subsequent turns; this models the well-documented psychological finding that negative events trigger retaliation, even when retaliation is strategically suboptimal.

-

Reputation Decay: serial stealers accumulated stigma (recall the point above about stealing thrice from your boss); your tenth steal costs more than your first, even if the victims were all different people. Everyone is watching, and everyone is keeping score.

-

Biased Selection: when opening wrapped gifts, agent did not choose uniformly at random, but weighted toward gifts that somehow looked good, be they bigger boxes, fancier paper. This (attempts to) model(s) the “judge a book by its cover” heuristic that humans obviously use and obviously should not.

Then I crossed these behavioral features with different preference structures: games where everyone wants different things (your trash is my treasure) versus games where everyone agrees on quality (everyone wants one thing, nobody wants the other).

Full factorial design: 16 feature combinations; 3 valuation models; 5,000 games each; 240,000 total simulations.

Finding 1: consensus creates carnage

Not all gift pools are equal. I simulated three different “valuation structures”: independent preferences; correlated preferences; negative correlated preferences:

- every player’s valuations are randomly generated; there is no correlation between what you want and what I want; in this way, one person’s trash really is another’s treasure;

- gifts have objective “quality” that everyone partially agrees on; personal taste still varies, but there is consensus that the $100 gift card is better than the novelty socks, for example; in this model, some gifts are just better;

- players split into camps with opposing tastes (the wine lovers and the teetotalers, for example). Your gain is not my loss, because I did not want that thing anyway.

Correlated preferences increased stealing by 47%.

When consensus exists, desirable gifts become contested resources. The early opener who unwraps something universally good becomes a target for everyone in the order; chains get longer as players fight over the same prizes, and the drama escalates!

Under independent preferences, conflict naturally dissipates: you steal the wine; I did not want the wine. I take the book; you did not want the book.

Negative correlation was the most peaceful. Almost definitionally, every steal takes something the victim would not have ranked highly in the first place; aggression is muted because the incentives do not collide.

If you want peace, curate gifts that are weird and subjective, things that will appeal intensely to specific people, but leave others cold. If you want a bloodbath, add one obviously premium item; that gift will be stolen four times and generate 80% of the evening’s drama.

Finding 2: shame governs everything

Consider: what stops people from stealing? I tested multiple hypotheses.

Is it uncertainty? Wrapped gifts are mysterious; maybe people avoid stealing because the bird in hand is not clearly better than the bush? As it turns out, partial information barely affected behavior. Stealing rates moved by less than 2%.

Is it strategic sophistication? Maybe smart players realize that restraint today means fewer enemies tomorrow? This is only partially observed, but not the main driver.

The real answer: social embarrassment. Enabling “social costs” in the simulation reduced stealing by 27–48%, depending on how much players agreed about gift quality; in this way, when everyone wants the same gifts, social costs cut stealing nearly in half.

The mechanism is intuitive upon reflection: each steal incurs a base awkwardness cost; stealing from the same person repeatedly compounds that cost; and overall reputation suffers with each theft, making future steals progressively more expensive.

Under these conditions, marginal steals become unprofitable. A gift that’s 10% better than yours is not worth the social friction; you need a substantial upgrade to justify the awkwardness.

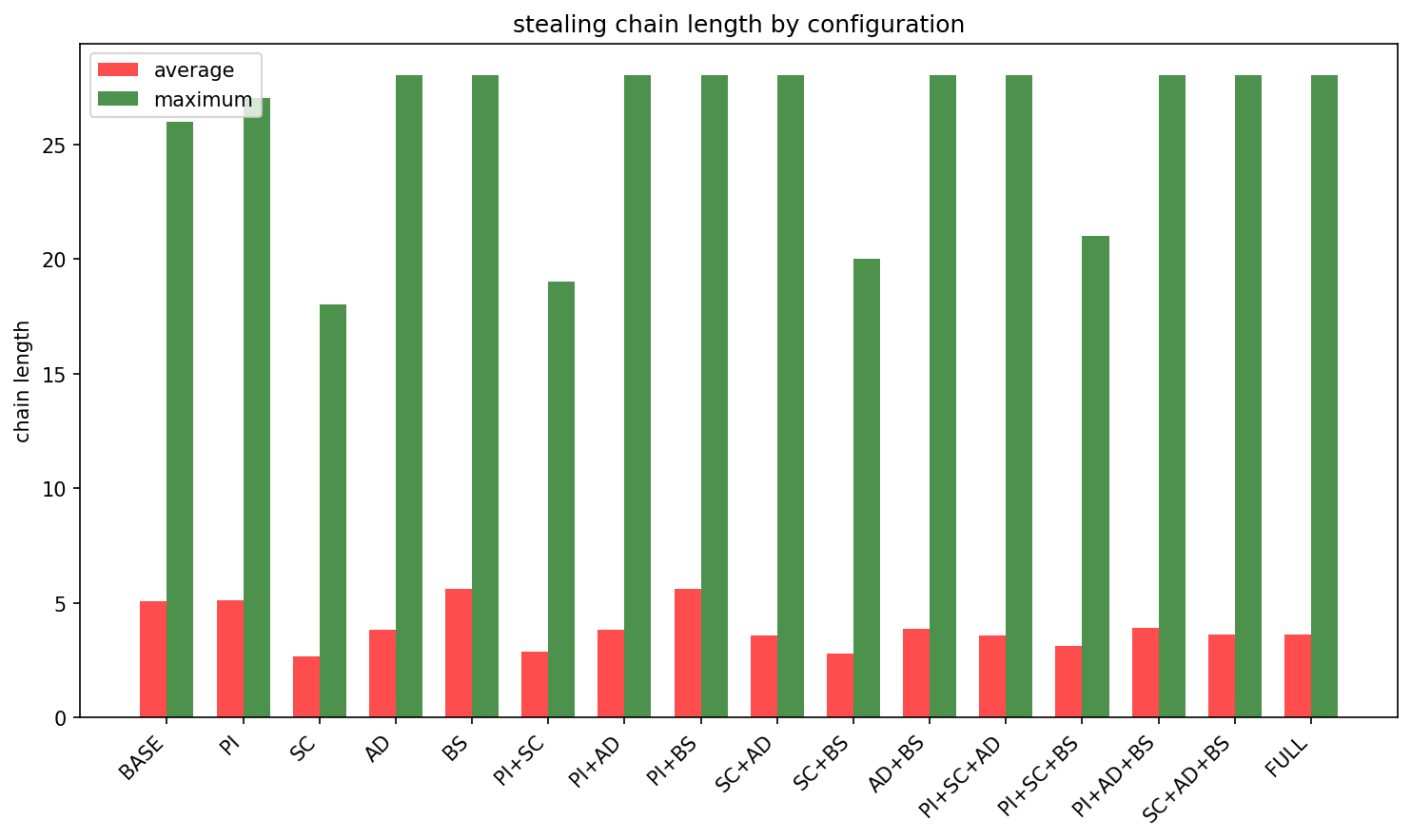

Distribution of length of steal chains for the independent valuation model

Distribution of length of steal chains for the independent valuation model

Distribution of length of steal chains for the correlated valuation model

Distribution of length of steal chains for the correlated valuation model

Distribution of length of steal chains for the negative correlated valuation model

Distribution of length of steal chains for the negative correlated valuation model

If you want a calm game, invite people who are easily embarrassed! If you want chaos, invite people with no shame!

Finding 3: Seat 2 is Charlie Brown’s

In going first, there is nothing to steal yet, so you are forced to open blind. But most rule variants compensate for this: Player 1 gets a final swap after everyone else has acted. They survey the complete landscape of opened gifts, then take whatever they want. No chain is triggered, and the game is over.

The final swap has significant implications. So who actually loses? Player 2. Across all 240,000 simulations, with every combination of features and valuation models:

-

Seat 1 achieves the highest average outcome; perfect information at game’s end; unlimited choice; no vulnerability to subsequent theft because the game ends.

-

Seat 2 has the lowest average outcome; they act when only one gift has been revealed; they are vulnerable to theft from every subsequent player. And they’re still vulnerable to Player 1’s final swap, essentially a double exposure that no other seat suffers.

-

Last seat (before the final swap) does relatively well: maximum information before acting, but they do remain exposed to Seat 1’s endgame move.

The positional inequity is stark. In games with correlated preferences (everyone agrees what’s good), Seat 1 achieved an average normalized value of 1.0, the theoretical maximum. Seat 2 averaged 0.67. That’s a 33% penalty for drawing the wrong number.

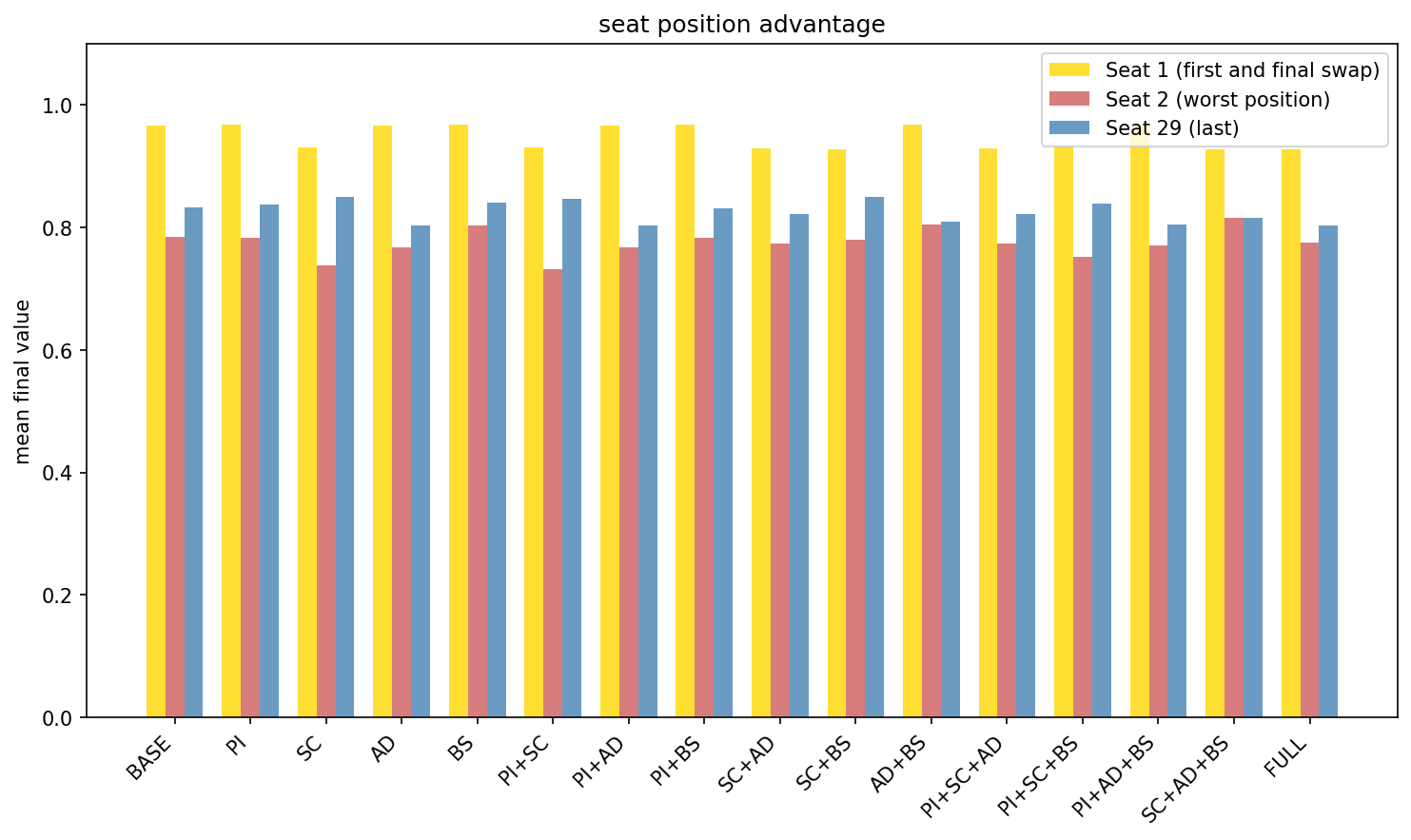

Distribution of scores for seat position for the independent valuation model

Distribution of scores for seat position for the independent valuation model

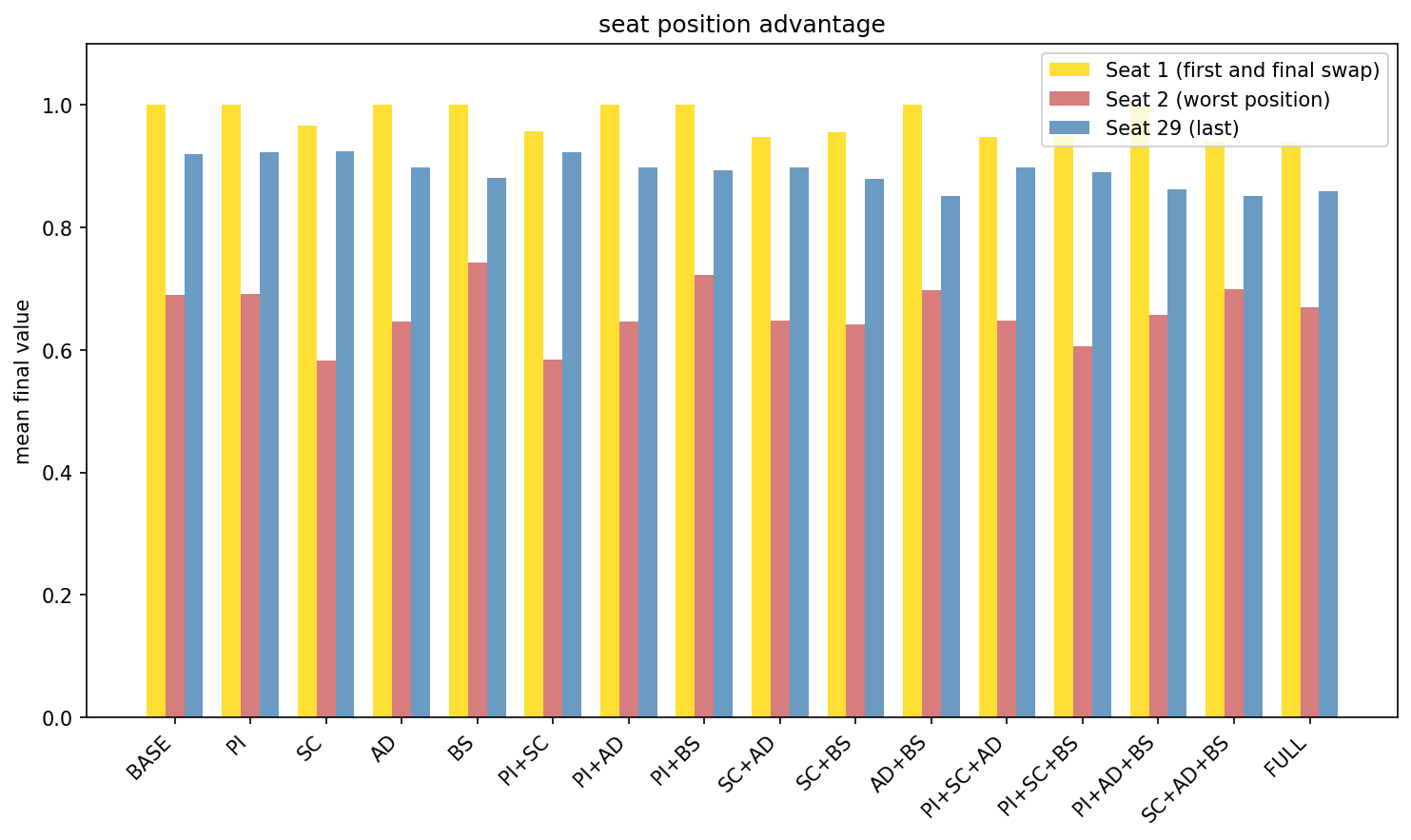

Distribution of scores for seat position for the correlated valuation model

Distribution of scores for seat position for the correlated valuation model

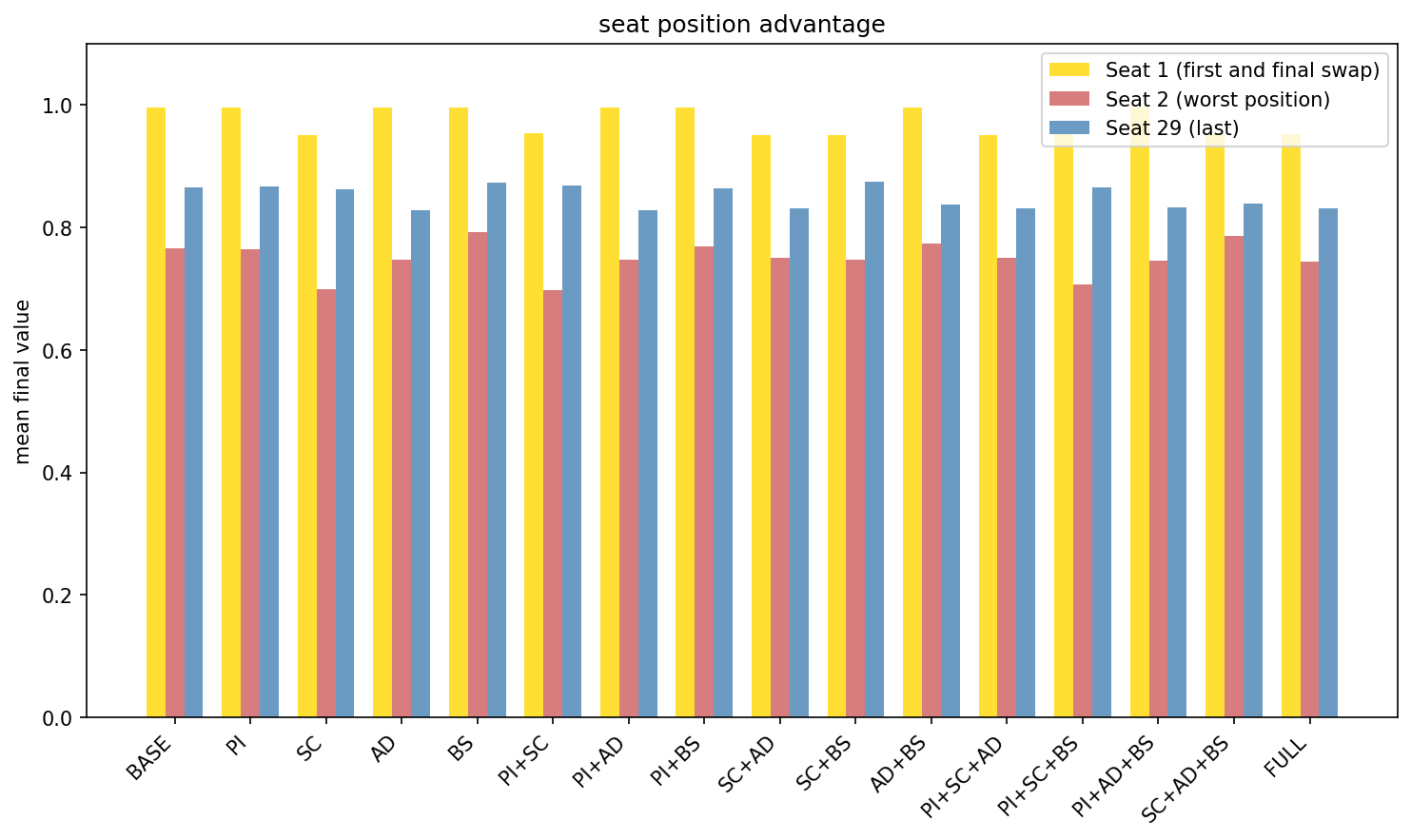

Distribution of scores for seat position for the negative correlated valuation model

Distribution of scores for seat position for the negative correlated valuation model

If you draw first, celebrate quietly. If you draw second, negotiate a trade, or offer to swap positions with someone in the middle who does not realize they’re getting a bad deal.

Finding 4: optimal strategy backfires

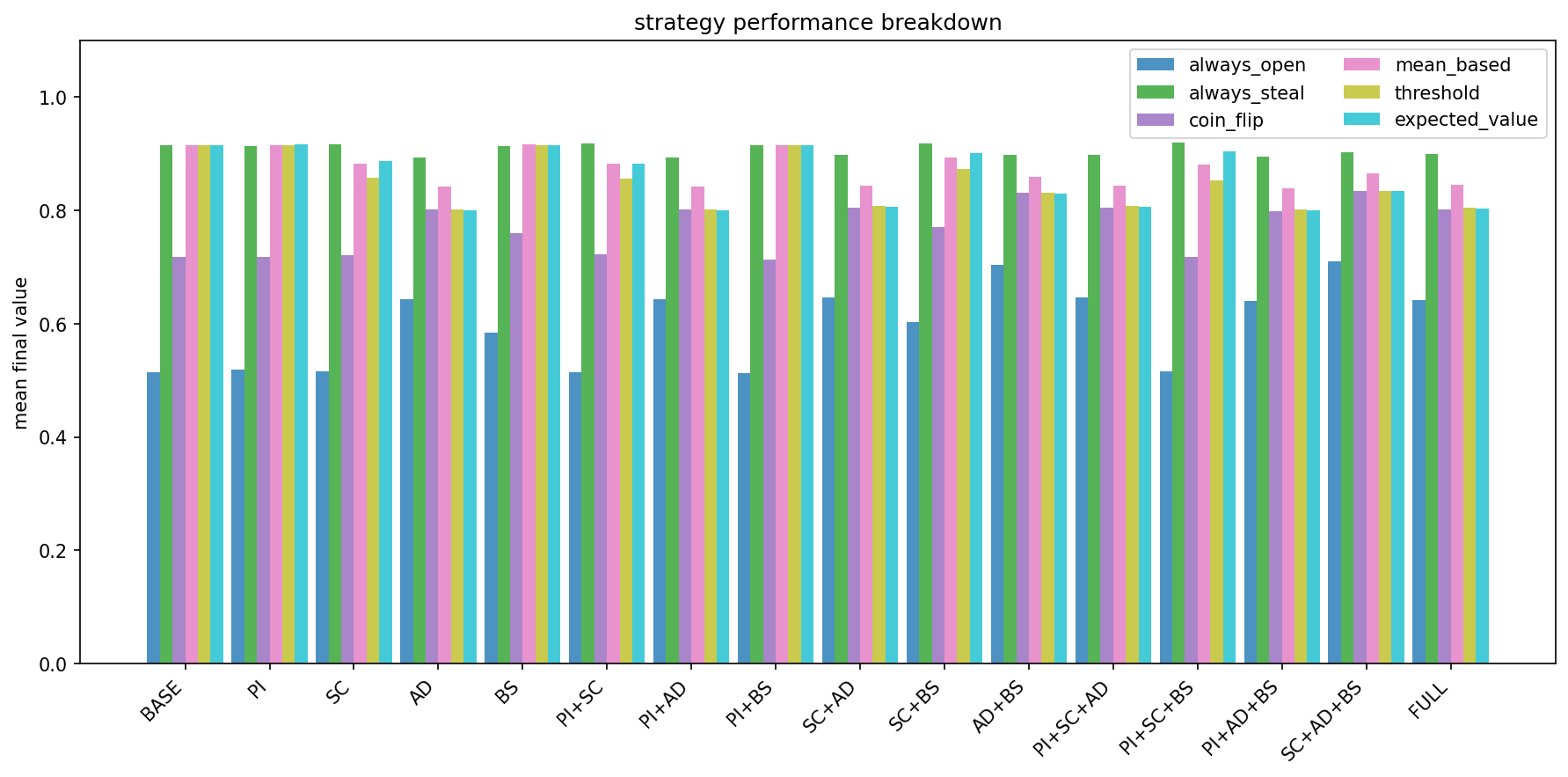

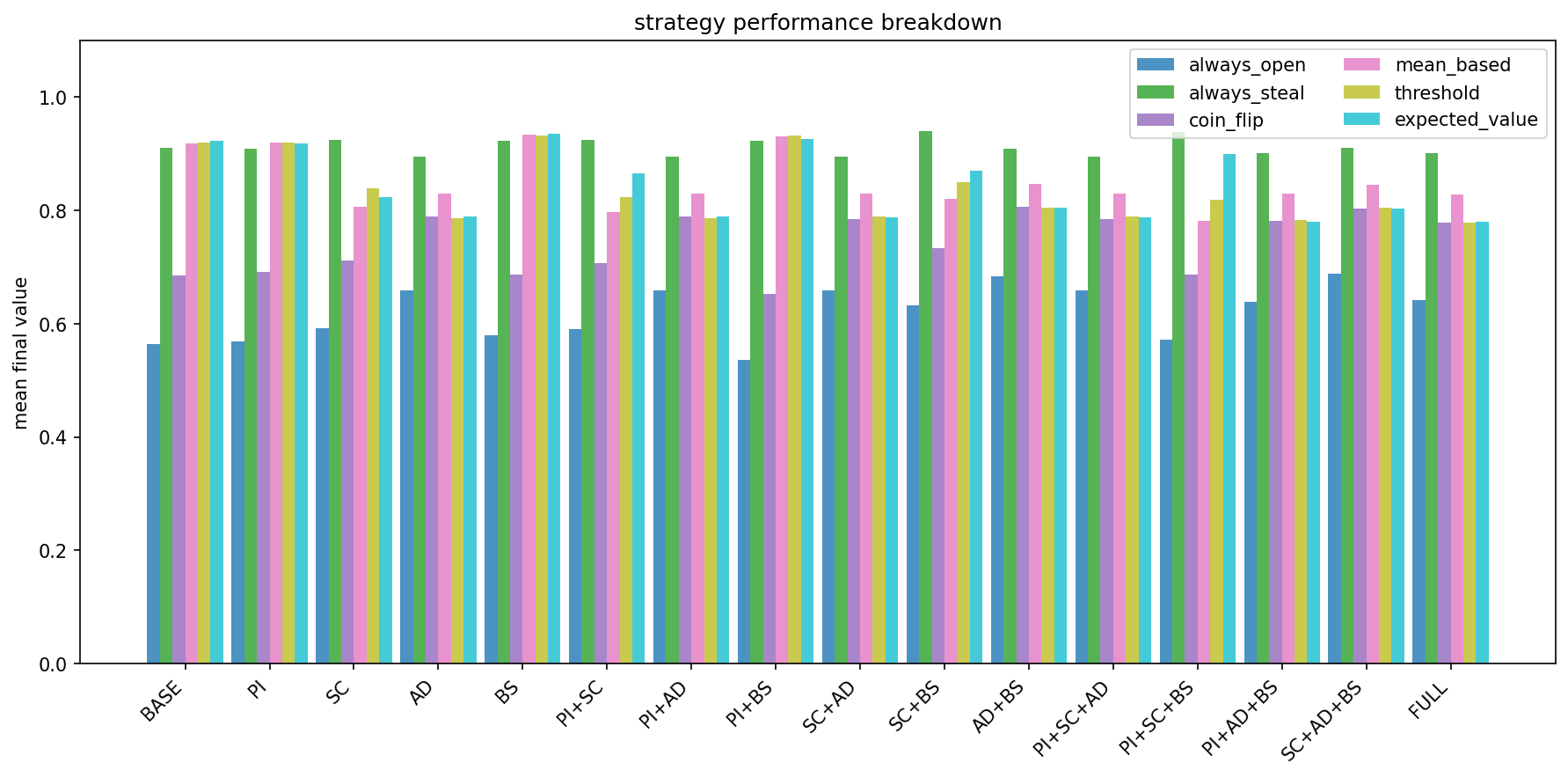

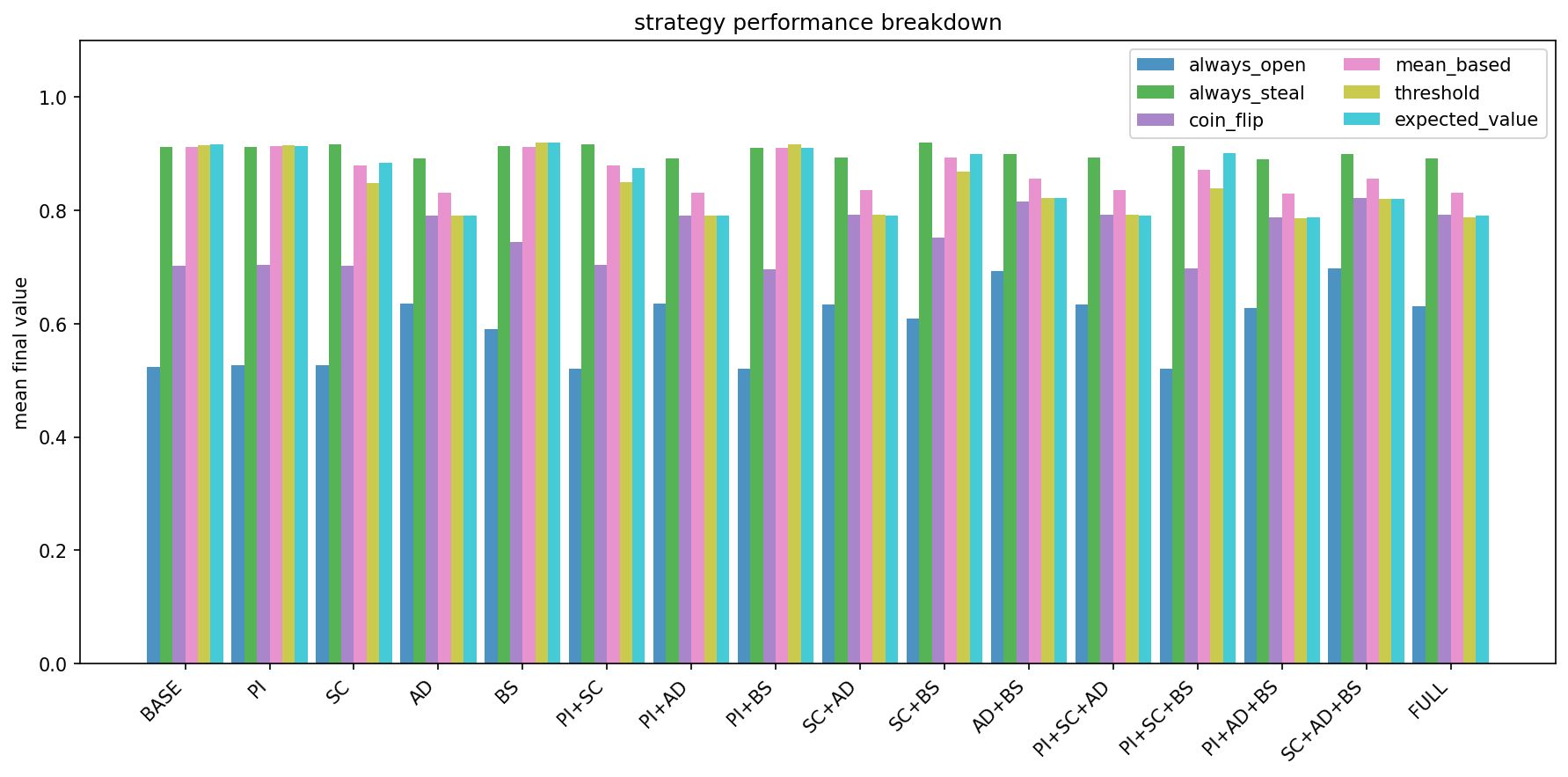

This is a counterintuitive result. I pitted six strategies against each other across all conditions:

- always_open is the pacifist who never steals unless forced;

- always_steal is the sociopath who always takes if a target exists;

- coin_flip is the chaos agent, 50/50 randomization;

- threshold is the steal only if the best available target exceeds a fixed quality bar;

- mean_based is the steal if the best target beats the average revealed gift;

- expected_value is the Bayesian optimizer that calculates whether stealing beats opening in expectation, accounting for uncertainty about wrapped gifts.

In the baseline game (in which there are no social costs, no frustration, no reputation), expected_value wins: it achieved the highest average outcome because it is doing exactly what decision theory says you should do: calculate expected utilities, choose the higher one.

But when I enabled frustration-aggression dynamics, where victims remember and retaliate, then the optimizer’s performance collapsed.

Under adaptive social dynamics, expected_value dropped by 13 percentage points: it went from the best strategy to middling. Meanwhile, simple strategies barely suffered: the always_steal approach lost only 1.6 points; the pacifist always_open actually improved by 9.5 points.

The question: why does sophistication fail?

The optimizer maximizes single-shot expected value without accounting for downstream retaliation; it looks at the current state, calculates that stealing yields +0.15 utility in expectation, and steals. This is correct in isolation, but triggers a grudge. The victim becomes more aggressive; on their next opportunity, they target the optimizer, and a cascade of mutual retaliation ensues.

The optimizer does not model this; rather, it treats each decision as independent, so it keeps making locally optimal choices that are globally catastrophic.

The aggressive strategy (always_steal) actually proves more robust! It does not pretend to be clever, it just relentlessly takes, which at least is predictable; other players learn to route around it.

Meanwhile, always_open benefits from never triggering retaliation. In a world where grudges are real, the pacifist’s ceiling is lower but so is their floor: they never get the best gift, but they never get targeted either.

In socially embedded games, sophistication backfires. This is an instance of “ecological rationality”, the idea that simple heuristics often outperform optimization when the environment includes factors the optimizer does not model.

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the independent valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the independent valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the correlated valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the correlated valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the negative correlated valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Distribution of scores for strategy relative to features for the negative correlated valuation model: PI partial information; SC social costs; AD adaptive dynamics; BS biased selection

Sometimes the best strategy is simple aggression; sometimes it is being nice enough that nobody targets you. The worst strategy is clever optimization that ignores social consequences; the optimizer is too smart for its own good.

Concluding remarks

Some implementation and strategy follows:

-

Hope for Seat 1 or whichever is the last seat. Avoid Seat 2 at all costs! If you draw second, try to trade positions with someone who has not thought about the math.

-

Do not trust fancy wrapping. Biased selection is real; people systematically open shiny-but-mediocre gifts early, leaving the understated packages, which may contain better items as much as those other packages, for later. Recomendation: if you are bringing a good gift, wrap it plainly.

-

Read the room on grudges. If your family holds grudges, moderate your aggression. One steal is fine; two steals from different people is fine; becoming the villain triggers retaliation cascades that cost more than you gain.

-

If nobody holds grudges, steal relentlessly! In a group of conflict-averse pacifists, the single aggressor cleans up; indulge in your villainy in this social setting: someone has to get the good stuff, might as well be you.

-

If you are hosting and want peace, curate for diversity. Weird, subjective gifts generate less conflict than obvious high-value items. When preferences diverge, everyone can get something they like without fighting.

-

If you are hosting and want entertainment, add a single premium item. It will be stolen repeatedly, and drama will ensue. You will have stories for next year.

This above all: it is supposed to be fun. The math is interesting, understanding the dynamics can help you play better. But if strategic optimization is ruining the vibe, you have missed the point. The relationships matter more than the outcomes.

Finally, let fun be not the least of things. The gift exchange game is a social game, where the primary objective is to have fun. Strategic elements should never supplant the game’s fundamental purpose of creating an entertaining gift-giving experience. Formalities here should always come a distant second to having fun with friends and family. Payers should feel free to make suboptimal choices that enhance the social experience. It is not that these are all mutually exclusive; understanding the game’s structure may encourage an appreciation and spark interesting discussions, but if competition compromises fun, then the former should be relaxed for the sake of latter. Have fun; please do not be that guy.

The full paper, including formal proofs, trajectory combinatorics, and complete simulation results, is available here.