On generalizing grounding (part 1)

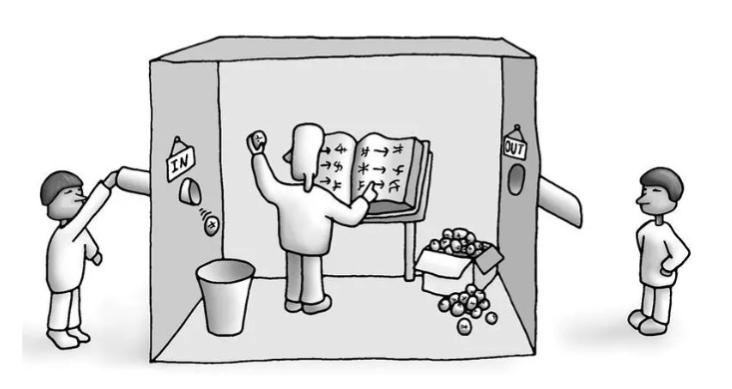

“Imagine a native English speaker who knows no Chinese locked in a room full of boxes of Chinese symbols (a data base) together with a book of instructions for manipulating the symbols (the program). Imagine that people outside the room send in other Chinese symbols which, unknown to the person in the room, are questions in Chinese (the input). And imagine that by following the instructions in the program the man in the room is able to pass out Chinese symbols which are correct answers to the questions (the output). The program enables the person in the room to pass the Turing Test for understanding Chinese but he does not understand a word of Chinese.” – John Searle, 1999

source: wikicommons

source: wikicommons

In 1980, John Searle imagined a man locked in a room, shuffling Chinese characters according to a rulebook. To outside observers, the room appears to understand Chinese, insofar as it takes questions in and produces sensible answers. The man inside understands nothing; he is just pattern-matching symbols. Stevan Harnad recast the parable into the symbol grounding problem: unless formal tokens connect to something beyond other tokens, definitions chase their own tails; in this way, each symbol is defined by more symbols, and meaning never arrives.

An embodied agent (e.g., you, me, a robot) told “pick up the red mug” must link red to visual data and mug to object affordances. Classical AI’s hand-coded symbols were meaningful to programmers, not to the systems manipulating them; embodied robotics proposed sensorimotor grounding; multimodal neural networks and reinforcement learning tie rewards to referential accuracy. Yet no consensus solution has emerged. Approaches address some aspects of grounding while neglecting others, and we often lack vocabulary to say precisely which aspects those are.

We are interested in, therefore, provisioning such a vocabulary. We recast grounding from a binary verdict (grounded or not) into a diagnostic audit across explicit criteria. The goal is not to settle metaphysical debates about the nature of meaning, but to give researchers, philosophers, computer scientists, linguists, a shared framework for stating claims precisely and testing them empirically.

This is part 1 of a series of posts walking through the paper On measuring grounding and generalizing grounding problems.

Consider: why accuracy is a poor proxy

Before introducing the framework, consider why we need one at all! An obvious candidate for measuring “understanding” in natural and artificial systems is accuracy: does the model get the right answer?

Accuracy is virtuous; it is concrete, comparable, and hard to fake on held-out test sets. But as a proxy for grounded understanding, it fails in instructive ways.

Accuracy rewards getting the right label on a fixed set of items; it quietly assumes the same trick will work when wording, context, or nuisance factors change. That assumption is often false. Small paraphrases degrade performance; typos cause disproportionate errors; shifts in context disrupt models even when original accuracy is high. The system that scores 95% on benchmark X may score 70% on a paraphrased version of benchmark X: same underlying task, different surface form.

In our terms, accuracy is at best one coordinate in a higher-dimensional audit: correlational faithfulness under a single evaluation tuple. It says nothing about whether internal states were shaped by task success, whether meaning is stable under realistic perturbations, or whether the system composes meanings systematically rather than memorizing each combination. Treating accuracy as a proxy for understanding mistakes a point for the curve; or, stars reflected in a pond at night for those in the sky.

Can accuracy be made meaningful with better test design? Certainly! Provided we build multiple parallel forms to enforce measurement invariance, systematically vary nuisance factors, and report full distributions rather than point estimates. That is, in effect, our proposal: make invariances and perturbations explicit, report the full profile, treat accuracy as one coordinate among several.

Grounding as audit

We define grounding as follows:

Grounding is the degree to which an agent’s own mechanisms implement and have acquired mappings from symbols to the task-appropriate meaning space, such that realized meanings align with intended ones, that alignment was selected-for because it causes task success, the mappings remain stable under declared perturbations, and are systematic under composition.

Several features of this definition matter: first, grounding is a matter of degree, not a binary; second, it is task-relative and context-indexed, in which a system may be well-grounded for (linguistic) tasks and poorly grounded for world-referential ones; third, it builds in both correlational and causal requirements, in that it is not enough for meanings to match, but that the matching must have been earned through a process that rewarded success.

We operationalize grounding through five desiderata, each evaluated relative to an evaluation tuple: (context k, meaning type t, threat model U, reference distribution P). The context specifies the particular situation; the meaning type specifies what kind of meaning is at stake (linguistic, world-referential, social-pragmatic); the threat model declares what perturbations we expect the system to withstand; the reference distribution specifies the population against which we measure.

The desiderata

G0 (authenticity) The relevant semantic mechanisms must reside inside the agent, not be supplied post-hoc by external analysts. We distinguish weak authenticity (mechanisms implemented inside the agent) from strong authenticity (mechanisms implemented and acquired through agent-internal learning or evolution).

This is a zeroth criterion because it gates the others. If semantics is smuggled in by an evaluator, if we interpret the system’s outputs charitably, supplying meanings the system itself doesn’t compute, then auditing the remaining criteria produces misleading results. It is cheating to consult a translator while claiming to speak Klingon!

G1 (preservation) Atomic symbols preserve their intended meanings through encoding and decoding. When the system processes red, mug, or left-of, the internal representations that result should still correspond to what those terms meant in context, within a declared error tolerance.

G2 (faithfulness) This has two parts.

G2a (correlational faithfulness) Realized meanings match intended meanings within tolerance. For a given context and meaning type, the system’s interpretation aligns with what a competent speaker/perceiver would intend.

G2b (etiological faithfulness) The internal mechanisms that produce this alignment were selected for success on the relevant task family. The system’s representations were shaped by feedback that rewarded accurate meaning.

The distinction between G2a and G2b matters. A lookup table might achieve perfect correlational faithfulness on its training distribution while having no etiological warrant for novel cases, so its “meanings” were not earned through interaction with the task.

G3 (robustness) Given an explicit threat model (typos, paraphrases, ASR noise, lighting changes, mild occlusions), small input perturbations yield bounded semantic change. Grounded systems degrade gracefully; ungrounded systems exhibit meaning whiplash, where minor surface variations cause disproportionate interpretation shifts.

G4 (compositionality) The meaning of a complex expression is determined (up to tolerance) by the meanings of its parts plus their mode of combination. A system that has learned left-of and behind separately should handle “the red mug behind the bowl” in a novel scene without having memorized that exact string.

A toy example

Consider the instruction: “Pick up the red mug to the left of the bowl.”

The context k is a particular kitchen: its layout, lighting, camera angle, speaker identity, time of utterance; the meaning type t is world-referential: does the phrase latch onto the correct physical object and spatial relation? The threat model U includes word-error from speech recognition, paraphrases (“grab the red cup on the bowl’s left side”), lighting variation, mild occlusion. The reference distribution P is a held-out set of kitchens such that we are not grading on training data.

Now the audit:

Authenticity (G0): Do the mechanisms mapping words to internal representations run inside the agent? In the weak form, the computation happens on-board. In the strong form, the agent acquired these mappings through training relevant to kitchen tasks, not through post-hoc annotation or external oracles.

Preservation (G1): Do single words retain their meanings through processing? When the system hears “red”, does its internal state correspond to redness-in-this-context? When it hears “left-of”, does the relational representation survive intact?

Faithfulness (G2): For the whole command, does the interpreted meaning match speaker intent (G2a)? Were the relevant representations shaped by feedback on this task family (G2b)?

Robustness (G3): If we inject perturbations from the threat model, swap “mug” for “cup”, add ASR noise, change lighting, does the system’s interpretation shift only slightly, or does it jump to a different object?

Compositionality (G4): Can the system handle novel combinations? If it knows “left-of” and “behind”, can it interpret “the red mug behind the bowl” in an unseen kitchen without having encountered that exact phrase?

What this framework is and is not

The framework is diagnostic; it provides vocabulary for stating grounding claims precisely and criteria for testing them. It does not resolve underlying metaphysical debates about whether meaning is ultimately narrow (supervening on internal states) or wide (constitutively involving world and social context). We remain neutral on that question here, though the desiderata can be indexed to different meaning types for investigators with different theoretical commitments.

A candid note: the framework is not as neutral as we might wish. G2b, the etiological criterion, imports substantive commitments from teleosemantics, the view that representational content is fixed by selection history. Requiring that meanings be “selected for” encodes a theory; indeed, investigators who reject teleosemantics will find G2b problematic! We flag this rather than hide it.

Grounding is also not general intelligence. The desiderata audit how meanings are established and maintained, not what a system can achieve. A model may be highly capable yet poorly grounded for certain tasks (if its competence derives from memorization rather than systematic representation, for instance). A model may be narrowly capable yet well-grounded within its domain (if that narrow capability reflects genuine semantic structure). Our criteria capture the former phenomenon, not the latter.

What comes next

This post introduced the problem and the diagnostic framework. Subsequent posts will apply the framework to three cases: model-theoretic semantics (which achieves exact compositionality but lacks etiological warrant); large language models (which show correlational faithfulness and local robustness for linguistic tasks, but face grounding gaps for world-referential meaning); human natural language (which meets the desiderata under strong authenticity through evolutionary and developmental acquisition).

The goal throughout is to replace the binary “X is or is not grounded” with a profile. Which desiderata does a system meet? Under what evaluation tuples? Where are the gaps? Grounding becomes something we can measure, compare, and improve, rather than something we argue about in the absence of a shared lexicon and shared criteria.

“Computation is defined purely formally or syntactically, whereas minds have actual mental or semantic contents, and we cannot get from syntactical to the semantic just by having the syntactical operations and nothing else…A system, me, for example, would not acquire an understanding of Chinese just by going through the steps of a computer program that simulated the behavior of a Chinese speaker.” – John Searle, 2010